共享资源:衍生作品

许多创意作品都是其他作品的衍生作品、有权拥有自己的版权。衍生作品是指不仅基于以前的作品,而且包含足够新的、有创造性的内容,从而有权拥有自己版权的作品。 不过,如果基础作品仍受版权保护,原始的版权持有者仍必须为基础作品的再使用授權。 换句话说,衍生作品并不仅仅是“基于”另一部作品的作品,衍生作品之所以被视为新作品,是因为在其创作过程中加入了某些相當多的新创造性内容--所有基于另一部以前的作品但缺乏重大的新创造性内容的后续作品,都只能被视为该作品的复制品,并不能因此享有新的版权保护,也不应被称为“衍生作品”,因为这在著作權权法中有非常明确的含义。

无论哪种情况,除非基础作品属于公共领域,或者有证据表明基础作品已被免费授权供重复使用(例如,在适当的創用CC授權條款下),否则作品的原创作者必须明确授权后才能将副本/衍生作品上传到共享資源。

In summary: you cannot trace someone else's copyrighted creative drawing and upload that tracing to Commons under a new, free license because a tracing is a copy without new creative content; likewise, you cannot make a movie version of a book you just read without the permission of the author, even if you added substantial creative new material to the storyline, because the movie requires the original book author's permission— if such permission were obtained, however, the movie would likely then be considered a derivative work entitled to its own novel copyright protection. "Derivative", in this sense, does not simply mean "derived from", it means, "derived from and including new creative content which is entitled to a new copyright."

什么是衍生作品?

Derivative works, according to the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, Section 101, are defined as follows:[1]

- "A 'derivative work' is a work based upon one or more pre-existing works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted. A work consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or other modifications, which, as a whole, represent an original work of authorship, is a 'derivative work'".

In short, all transfers of a creative, copyrightable work into a new medium (i.e., from book to movie) as well as all other modifications of a work whose outcome is a new, creatively original work (e.g., from Shakespearean play into a modern rendition of a Shakespearean play with new wording or characters) are considered derivative works entitled to their own, new copyrights. Who is allowed to create such works? According to U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, Section 106:

- "(T)he owner of copyright under this title has the exclusive rights to do and to authorize any of the following: (...) (2) to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work".

Unlike an exact copy or minor variation of a work (e.g. the same book with a different title), which would be considered a mere copy and would not result in a new copyright, a derivative work creates a new copyright on all original aspects of the new version. Thus, for example, the creator of The Annotated Hobbit holds a copyright on all of the notes and commentary he wrote, but not on the original text of The Hobbit, which is also included in the book, the copyright to which is owned by the Tolkien Estate. The original Estate copyright still holds, and then the annotations also acquire a new and independent copyright of their own.

Likewise, the corporation that holds the copyright to Darth Vader (i.e., Walt Disney) has the exclusive right to create or authorize any derivative works of that character, including photographs or drawings of him which portray him in novel and creative ways, since (as court decisions put it) that is one aspect of the copyright holder's work that they might want to exploit commercially. In the same manner, anyone can make a movie based on The Bible, and may make their own movie called "The Ten Commandments" based on the Biblical chapter Exodus, but may not make a new version of the 1956 film, "The Ten Commandments", even with substantial new creative input, without getting permission of Paramount Pictures (the copyright holder).

如果我用自己的相机给一个物体拍照,我就拥有这张照片的版权。我不能自行选择版权许可吗?为什么我要担心其他版权所有者?

By taking a picture with a copyrighted cartoon character on a T-shirt as its main subject, for example, the photographer creates a new, copyrighted work (the photograph), but the rights of the cartoon character's creator still affect the resulting photograph. Such a photograph could not be published without the consent of both copyright holders: the photographer and the cartoonist.

It does not matter if a drawing of a copyrighted character's likeness is created entirely by the uploader without any other reference than the uploader's memory. A non-free copyrighted work simply cannot be rendered free without the consent of the copyright holder, not by photographing, nor drawing, nor sculpting (but see 共享资源:全景自由).

Locations such as theme parks usually allow photography and sometimes even encourage it even though items of copyrighted artwork will almost certainly be included in visitors' photos. Such policies, however, do not automatically mean that such photos can be distributed under a public domain dedication or a free content license; the intent of a venue allowing photography may be to facilitate photography for personal usage and/or non-commercial sharing on social networking sites, for example. (See this discussion.) Also, the legal concept of de minimis can apply in such a setting: if the subject of your theme park photograph is your daughter eating an ice cream but someone in a Mickey Mouse costume can be seen in the background, this is not considered infringement nor a derivative work so long as it is clear from the photograph that you are interested in the girl and the frozen treat rather than the oversized rodent, and you may even market that image commercially (though you must be sure that Mickey really is "de minimis" and his presence must not make that image more useful, more interesting, or more marketable than it would be without him).

如果我拍了一张拿着小熊维尼毛绒玩具的孩子的照片,迪士尼是否会因其拥有小熊维尼的设计而拥有照片的版权?

不會,迪士尼沒有拥有照片的版权。這裏有两种不同的版权需要分开考虑:一是摄影师的版权(照片),二是迪士尼的版权(玩具)。你必须把它们分清楚。问问你自己:这张照片是否可以作為“小熊维尼”的图示吗?我是否是想透过玩具的照片来规避维尼二维照片的限制?如果是这样,那就不行。

但要注意的是,迪斯尼的保护策略既依赖于作者的权利(艺术财产)、也依赖于商标(扩展到保护外观设计)。在这种情况下,实际的法律分析会更加微妙。 虽然迪斯尼并不拥有照片的版权,但憑藉著照片的复制就有可能侵犯迪斯尼对维尼的版权。由于几乎所有的摄影作品都被认为至少涉及到摄影师的一点创造性,因此事实上,你可能在未经授權的情况下创作了一個衍生作品。

不是所有事物都由某人持有版权了嗎?那车呢?厨房的椅子呢?我的电脑机殼呢?

不是的。美国版权法中有特殊规定,可在很大程度上豁免实用物品的版权保护:

修正案第二部份规定: “有用物品的设计[...]只有在下列情况下才应被视为图像、图形或雕刻作品:这种设计包含的图像、图形或雕刻特征可以与物品的实用性分开识别,并且能够独立于物品的实用性而存在”。

A "useful article" is defined as "an article having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information." This part of the amendment is an adaptation of language added to the Copyright Office Regulations in the mid-1950's in an effort to implement the Supreme Court's decision in the Mazer case.

In adopting this amendatory language, the Committee is seeking to draw as clear a line as possible between copyrightable works of applied art and non-copyrighted works of industrial design. A two-dimensional painting, drawing, or graphic work is still capable of being identified as such when it is printed on or applied to utilitarian articles such as textile fabrics, wallpaper, containers, and the like. The same is true when a statue or carving is used to embellish an industrial product or, as in the Mazer case, is incorporated into a product without losing its ability to exist independently as a work of art. On the other hand, although the shape of an industrial product may be aesthetically satisfying and valuable, the Committee's intention is not to offer it copyright protection under the bill. Unless the shape of an automobile, airplane, ladies' dress, food processor, television set, or any other industrial product contains some element that, physically or conceptually, can be identified as separable from the utilitarian aspects of that article, the design would not be copyrighted under the bill.

The test of separability and independence from "the utilitarian aspects of the article" does not depend upon the nature of the design—that is, even if the appearance of an article is determined by aesthetic (as opposed to functional) considerations, only elements, if any, which can be identified separately from the useful article as such are copyrightable. And, even if the three-dimensional design contains some such element (for example, a carving on the back of a chair or a floral relief design on silver flatware), copyright protection would extend only to that element, and would not cover the overall configuration of the utilitarian article as such.

- From Cornell University Law School notes on US Code 17 § 102; content primarily taken from a U.S. Government work

- Note that while the commentary above was apparently written while some language was an amendment which had not then been enacted, it was subsequently enacted and can be found in 17 USC 101.

Sculptures, paintings, action figures, and (in many cases) toys and models do not have utilitarian aspects and therefore in the United States (where Commons is hosted) such objects are generally considered protected as copyrighted works of art. A toy airplane, for example, is mainly intended to portray the appearance of an airplane in a manner similar to that of a painting of an airplane.[2] On the other hand, ordinary alarm clocks, dinner plates, gaming consoles— as well as actual, full-scale planes— are not generally copyrightable... though any design painted on the dinner plate would likely be subject to copyright protection, as would an alarm clock in the shape of Snoopy the dog.

It is possible for utilitarian objects to have aspects which are copyrightable, but there is no clear line in US law between works which are copyrightable and objects which are not.[3] A white paper on copyright and 3D printing mentioned several US court rulings that were each about whether a functional object had artistic elements that were "physically or conceptually" separable from the object's functional aspects and therefore copyrightable. The whitepaper suggested a consideration for determining if specific elements of a utilitarian object are copyrightable under US law: if an object has non-functional elements, then those elements are more likely to be copyrightable if the design of the elements was not influenced by utilitarian pressures.[4]

Different countries may have different definitions: German law has a term called Schöpfungshöhe, which is the threshold of originality required for copyright protection. In the vast majority of national jurisdictions, the level of originality required for copyright protection of works of applied arts does not differ from the one for the fine arts.[5] It is higher in Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, Slovenia, and Switzerland.[5][6] There is no legal definition for this threshold, so one must use common sense and existing case law.[7]

Instead of copyright protection, utilitarian objects are generally protected by design patents, which, depending on jurisdiction, may limit commercial use of depictions. However, patents and copyright are separate areas of law, and works uploaded to Commons are only required to be free with respect to copyright. Therefore, patents of this kind are not a matter of concern for Commons.

Photos of people in costumes of copyrighted characters may or may not be copyrighted.[8] See 共享資源:各種題材的著作權法規#Costumes and cosplay for more information. These should be decided on a case-by-case basis using the separability test.[2]

文本

复制受版权保护的书籍、文章或类似作品等非自由媒体的文本是被禁止的。然而,信息本身是不受版权保护的,您可以自由地用自己的话重写它。若是篇幅有限并注明出处的話,则引用是可允许的。

我知道不能上传有著作权的艺术品(比如画作和雕像),但玩具呢?玩具又不是艺术品!

参见:Category:Toys related deletion requests 尽管版权的范围因国家而略有差异,但认为版权仅适用于“艺术品”是一种误解。相反,版权通常适用于更多种类的作品;以维基媒体基金会服务器所在的美国为例:版权保护适用于“固定在任何有形表达媒介中的原创作品”[9]。事实上,玩具通常是原创的(源于作者)、有作者的(人类创作者)、并固定在有形介质(木头、织物等)中。

那么,问题在于玩具是否应被视为交通工具和家具:因其本質上為实用物品而免受版权保护。 事实上,在某些国家,如日本,[10] 一般认为玩具是实用物品,因此没有资格获得版权。 但其他国家,如美国,则不认为玩具是实用物品。 因此,绘画、雕像和玩具都是受版权保护的作品,其照片需要原创作者的许可才能在共享资源上发布。 如同您不能上传毕加索雕塑的照片一样,您也不能上传米老鼠或神奇宝贝的照片。

The legal rationale in the United States has been established in numerous cases. "Gay Toys, Inc. versus Buddy L Corporation", for example, found "a toy airplane is to be played with and enjoyed, but a painting of an airplane, which is copyrightable, is to be looked at and enjoyed. Other than the portrayal of a real airplane, a toy airplane, like a painting, has no intrinsic utilitarian function."[11] Additional rulings have found, for example, "it is no longer subject to dispute that statues or models of animals or dolls are entitled to copyright protection"[12] and "There is no question but that stuffed toy animals are entitled to copyright protection."[13]

Similarly, dolls' clothing has been found to be copyrightable in the US on the grounds that it does not have a utilitarian function of providing protection from the elements or preserving modesty in the manner that clothing for humans does (the latter is a "useful article.")[2] Numerous lawsuits have shown that Mickey Mouse or Asterix have to be treated as works of art, which means they are subject to copyright, while a common spoon or a table are not works of art. Artistic elements of these items could be copyrighted, but only if it's separable from the utilitarian elements.[14] Some toys are also too simple to meet the threshold of originality, for example, the Kong dog toy.[15] "A toy model that is an exact replica of an automobile, airplane, train, or other useful article where no creative expression has been added to the existing design" is not eligible for copyright protection in the United States.[16]

In other cases, the "separability" test may be needed (see Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc.). Consensus on Commons has found that sex dolls are copyrightable, as their design elements are separable from their utilitarian function.

When uploading a picture of a toy, you must show that the toy is in the public domain in both the United States and in the source country of the toy. In the United States, copyright is granted for toys even if the toy is ineligible for copyright in the source country.[17]

但是维基共享资源不是商业性网站!什么是合理使用?

维基共享资源不是商业性质的项目,但我们的项目范围要求所有文件都能自由地被商业使用,不会与第三方之间产生版权纠纷。 合理使用在维基共享资源不被允许。合理使用是一个困难的合法例外,仅适用于在有限上下文中使用的相关图片。它永远不适用于受版权保护的材料的整个数据库。

但没有图片的话我们怎么描述星球大战或者宝可梦这种主题?

确实,为此类条目增加插图可能很难甚至不可能。不过,条目还是可以写的。它们没有插图并不影响维基媒体项目的活力。而且,有很多主题可以创建不侵犯第三方版权的插图。 即使是您自己绘制的皮卡丘也不能以自由版权协议发布。

Some Wikimedia projects allow non-free works (including derivatives of non-free works) to be uploaded locally under fair use provisions. The situations in which this is permitted are strictly limited. It is vital to consult the policies and guidelines of the project in question before attempting to invoke fair use claims.

公共领域作品中受版权保护的角色图呢?

Sometimes individual works featuring copyrighted characters (such as Mickey Mouse or Superman) enter the public domain. Although the works themselves are in the public domain, any portions that include the copyrighted characters are still restricted by copyright law.[18][19]

This concept even extends to non-sentient "characters", such as the Batmobile.[20] Derivative representations of characters are protected by copyright law in the United States until the original work that created the character is no longer copyrighted.[21] This protection is separate from trademark protection. See Commons:Character copyrights for information on the copyright status of specific characters.

I've never heard about this before! Is this some kind of creative interpretation?

Actually, no. Photographs of, say, modern art statues or paintings cannot be uploaded either, and people accept that. If we accept the legal standard that comic figures and action figures can be considered as art and thus are copyrighted, we are just applying the standard rule here.

Casebook

参见:共享資源:各種題材的著作權法規.

How does this guideline concern the selection of images that are allowed on Wikimedia Commons?

- Comic figures and action figures: No photographs, drawings, paintings or any other copies/derivative works of these are allowed (as long as the original is not in the public domain). No pictures are allowed of items which are derivatives from copyrighted figures themselves, like dolls, action figures, T-shirts, printed bags, ashtrays etc.

- Paintings with frames: Paintings that are in the public domain are generally allowed (see 共享资源:许可协议). Frames are 3-dimensional objects, so the photo may be copyrighted. Remember: Always provide the original creator's name, birth and death date and the time of creation, if you can! If you do not know, give as much source information as possible (source link, place of publication etc.). Other volunteers must be able to verify the copyright status. Furthermore, the moral rights of the original creator—which include the right to be named as the author—are perpetual in some countries. In either case you need permission from the author to create a derivative work. Without such permission any art you create based on their work is legally considered an unlicensed copy owned by the original author (taking from another web site is not allowed without their permission).

- Cave paintings: Cave walls are usually not flat, but three-dimensional. The same goes for antique vases and other uneven or rough surfaces. This could mean that photographs of such media can be copyrighted, even if the cave painting is in the public domain. (We are looking for case studies here!) Old frescoes and other paintings on flat surfaces in the public domain should be fine, as long as they are reproduced as two-dimensional artworks.

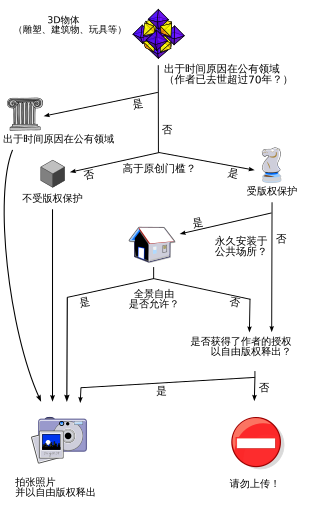

- Photographs of buildings and artworks in public spaces: Those are derivative works, but they may be OK, if the artwork is permanently installed (which means, it is there to stay, not to be removed after a certain time), and in some countries if you are on public ground while taking the picture. Check 共享资源:全景自由. If your country has a liberal policy on this exception and learn more about freedom of panorama. Note that in most countries, freedom of panorama does not cover two-dimensional artworks such as murals.

- Replicas of artworks: Exact replicas (even poor ones) of public domain works, like tourist souvenirs of the Venus de Milo, cannot attract any new copyright as they do not have the required originality. Hence, photographs of such items can be treated just like photographs of the artwork itself.

- Photographs of three-dimensional objects: always copyrighted, even if the object itself is in the public domain. If you did not take the photograph yourself, you need permission from the owner of the photographic copyright (unless of course the photograph itself is in the public domain).

- Images of characters/objects/scenes in books: subject to any copyright on the book itself. You cannot freely create and distribute a drawing of Albus Dumbledore any more than you could distribute your own Harry Potter movie. In either case you need permission from the author to create a derivative work. Without such permission any art you create based on their work is legally considered an unlicensed copy owned by the original author.

- Fan art: See 共享资源:粉丝艺术

标记非自由衍生作品

如果您在维基共享资源上发现非自由作品的衍生作品,请将它们标记为{{SD|F3}}以便快速删除。

參見

- Collages are combinations of multiple images arranged into a single image

- Screenshots are a type of derivative work

參考資料

- ↑ U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, Section 101. Retrieved on 2019-04-17.

- ↑ a b Pearlman, Rachel (2012-09-17). IP Frontiers: From planes to dolls: Copyright challenges in the toy industry. NY Daily Record. Retrieved on 2014-06-21.

- ↑ Weinberg, Michael (January 2013). What's the Deal with Copyright and 3D Printing? 9. Public Knowledge. Retrieved on 2016-09-22.

- ↑ Weinberg, Michael (January 2013). What's the Deal with Copyright and 3D Printing? 13. Public Knowledge. Retrieved on 2016-09-22.

- ↑ a b Summary Report: The Interplay Between Design and Copyright Protection for Industrial Products 4–5. AIPPI.

- ↑ VSL0069492. Retrieved on 29 October 2013.

- ↑ Compendium II: Copyright Office Practices - Chapter 500. University of New Hampshire School of Law.

- ↑ Commons:Deletion requests/Images of costumes tagged as copyvios by AnimeFan#Comment by Mike Godwin

- ↑ 17 U.S. Code § 102. Subject matter of copyright: In general. Retrieved on 2019-04-17.

- ↑ "Farby" doll is judged not to be a work of art. Sendai High Court (9 July 2002). Retrieved on 2019-04-17.

- ↑ (Gay Toys, Inc. v. Buddy L Corporation, 703 F.2d 970 (6th Cir. 1983)

- ↑ Blazon, Inc. v. DeLuxe Game Corp., 268 F. Supp. 416 (S.D.N.Y. 1965)

- ↑ R. Dakin & Co. v. A & L Novelty Co., Inc., 444 F. Supp. 1080, 1083-84 (E.D.N.Y. 1978)

- ↑ [1] Public domain maps]. Public Domain Sherpa. Retrieved on 2019-04-17.

- ↑ Kong Design (20 September 213). Retrieved on 2019-04-17.

- ↑ Compendium III § 313.4(A)

- ↑ HASBRO BRADLEY, INC. v. SPARKLE TOYS, INC., 780 F.2d 189 (2nd Cir. 1985).

- ↑ Siegel v. Warner Bros (2009)

- ↑ Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. v. American Honda Motor Co. (1995)

- ↑ DC Comics v. Mark Towle (2013)

- ↑ Warner Bros. v. AVELA (2011)

外部链接

- Case studies

- https://casetext.com/case/ty-inc-v-publications-international-5 (Citing a court case in which photographs of Beanie Baby dolls are treated as derivative works)

- http://www.benedict.com/visual/batman/batman (Citing a court case in which Warner Bros was accused of copyright infringement for filming a statue inside a building)

- http://lawspace.stmarytx.edu/files/original/Gorman.pdf (Eric D. Gorman: How to determine whether appropriation art is transformative “fair use” or morely an unauthorized derivative?)

- Other useful sites

- Derivative Works :: Topics :: Lumen (formerly Chilling Effects)

- L.H.O.O.Q.--Internet-Related Derivative Works

- US Copyright Office Circular 14 - Copyright in Derivative Works and Compilations

- Compendium II: Copyright Office Practices - Chapter 500 (What's copyrightable and what's not in the area of visual arts)

- Australian Copyright Council's Online Information Centre has many downloadable guides covering aspects of copyright.